For a lactate curve, three shifts are possible: to the left, to the right, or none at all.

A traditional interpretation of those shifts would be, respectively, a decrease in aerobic capacity, an increase, and no change. But by only considering aerobic capacity, a traditional interpretation is never complete and has a 40% chance of being wrong.1

"The traditional way to read a curve is that a shift to the right in the curve means ... better endurance, and a shift to the left means deteriorating endurance. The problem with that idea is it is too simplistic."

—Steve Magness, The Science of Running

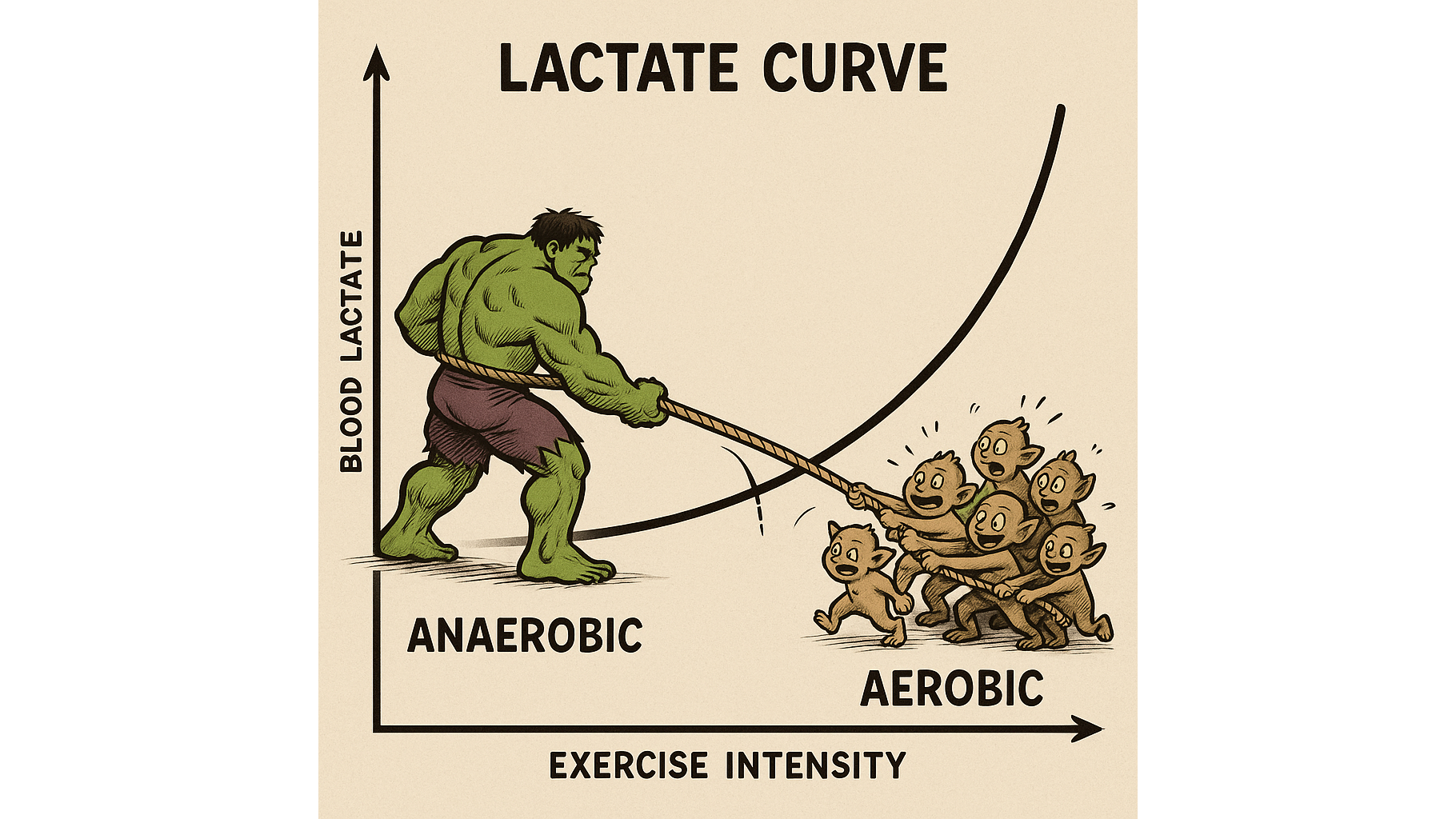

As Magness suggests, a lactate curve is not a single index. It is a series of balance points between two opposing forces. Each reading represents the tension between anaerobic capacity (pulling the value to the left) and aerobic capacity (pulling the value to the right).

It's the difference between the two.

It's not the absolute strength of either capacity that determines a lactate reading, but the relative strengths of both. Anaerobic capacity increases the amount of circulating lactate and aerobic capacity decreases it. So the observed lactate in the bloodstream is not an absolute value for either, but the difference between the two.

- [La produced] - [La cleared] = [La observed]

Lactate from glycolysis enters the bloodstream where a portion is cleared via aerobic metabolism. What's left behind is what is measured in a lactate sample. So measured lactate is only the difference between the two capacities. It's not a clear indication of the absolute strength of either one.

At a constant speed, changes in blood lactate only reveal that the balance has shifted. On its own, a lactate curve can never explain the reason for its shift. Because of this, 13 possible reasons exist, not three: five for an increase, five for a decrease, and three for no change at all.2

Reasons for a Shift

A shift to the left means that the balance has tipped toward anaerobic capacity, and the difference in lactate has increased. That change could come from:

| AnC | AeC | Shift | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ++ | + | < | An increase in AnC with a lesser increase in AeC |

| + | = | < | An increase in AnC with no change in AeC |

| + | - | < | An increase in AnC with a decrease in AeC |

| = | - | < | No change in AnC with a decrease in AeC |

| - | -- | < | A decrease in AnC with a greater decrease in AeC |

A shift to the right means that the balance has tipped toward aerobic capacity, and the difference in lactate has decreased. That change could come from:

| AnC | AeC | Shift | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| -- | - | > | A decrease in AnC with a lesser decrease in AeC |

| - | = | > | A decrease in AnC with no change in AeC |

| - | + | > | A decrease in AnC with an increase in AeC |

| = | + | > | No change in AnC with an increase in AeC |

| + | ++ | > | An increase in AnC with a greater increase in AeC |

No shift means that the balance is unchanged, and the difference in lactate has remained the same. That could come from:

| AnC | AeC | Shift | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | + | = | An equal increase in both AnC and AeC |

| = | = | = | No change in either AnC or AeC |

| - | - | = | An equal decrease in AnC and AeC |

The reason can't be known from the curve itself.

It should never be assumed that a change in only one factor—traditionally, aerobic capacity—is responsible. The true cause must be inferred from other factors.3

A lactate curve on its own cannot reveal whether aerobic or anaerobic changes are responsible. Only a complete test protocol can.4

- "...only about 60% of the classic interpretations of the aerobic capacity fits with the more sophisticated valuation. This means that out of five lactate tests classically evaluated, on average two interpretations are incorrect and will inevitably lead to wrong training advice." Jan Olbrecht, The Science of Winning, p.145

- Jan Olbrecht originally wrote about this apparent paradox in 2000, but the traditional interpretation has persisted long after. For a table that illustrates all 13 possibilities, see page 112 in The Science of Winning.

- The two capacities—aerobic and anaerobic—can really only be measured in a lab, respectively by VO2max and VLamax. But precise tests are expensive, inconvenient, and interrupt the training process. In contrast, regular Olbrecht-style tests can provide similar information by proxy and without a negative impact on a macrocycle.

- A complete lactate test must include samples at submaximal intensities—for aerobic capacity—and a near-maximal sample to reflect anaerobic capacity. Olbrecht recommends a full recovery, an all-out 45-90" effort, and then samples until a peak value is observed.

- The longer an event, the slower the average pace, and the less the anaerobic contribution. So for many mountain athletes, not measuring anaerobic capacity may be lower risk. But tracking the change in both capacities will provide a fuller picture than tracking only one.

- Regardless of the role of anaerobic capacity during a goal event, training anaerobic capacity is a worthwhile training component for strength, speed, and—according to Olbrecht—to add “spice” to aerobic capacity workouts, increasing the aerobic stimulus.